Throughout World Trade Month this May, the U.S. Grains Council (USGC) and its members have reflected on the value of trade to the grains sector and the U.S. economy. The following excerpt of “Backgrounder: The Essential Guide To U.S. Trade,” published last year by the Council and the National Corn Growers Association (NCGA), looks at three of trade’s first principles: specialization, reciprocity and value creation that benefits both parties to the exchange.

Look for the trade value in everything. Most products we use have stories. They are the culmination of ideas, engineering, materials testing, accounting services, design, coding, sales, farming, manufacturing and countless other activities by workers who add their value along the way.

Examples can be found all around your home. Open your dresser drawer. Chances are, you’ll pull a cotton shirt out of your drawer that doesn’t have a “Made in USA” label. Even so, American researchers, engineers and designers in the textile industry are busy figuring out how our jeans can hold up through a lot of washings, how to keep wrinkles out of our suit jackets, and how our yoga pants will stretch in downward dog. Even if American workers aren’t stitching up the final product when the “Made in” label is sewn in, they are nonetheless responsible for creating around 70% of that garment’s value.

Every industry is different, but the basic story is similar: the expansion of global production networks offers opportunities for a wide range of American workers to participate. The question is, where do American workers want to be on the production curve? Most jobs are being created at the beginning of the product journey and at the end, closer to customers. Fortunately, this is where American companies and workers excel and where jobs are being created.

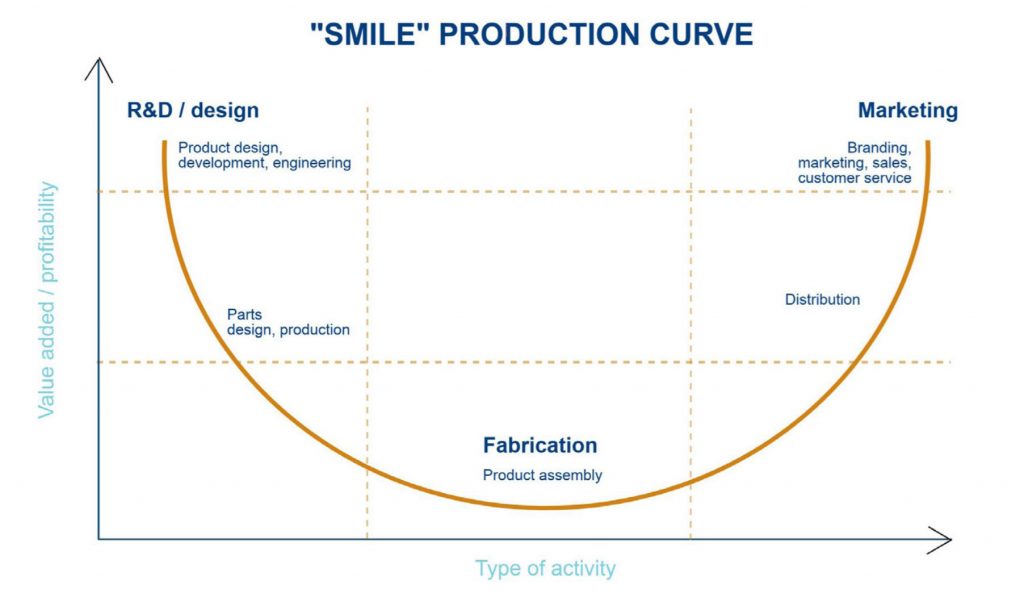

Americans stake out high ground in value chains. The global production of goods can be charted based on stages of activity and where value is added. Such a graph is called the “smile curve,” with high-value activities at the beginning of a product’s life, to low-value activities when products are fabricated, returning to more high-value activities as the product moves closer to the consumer through marketing and distribution.

The great news is Americans compete most effectively performing the activities on the production curve that require the most creativity and know-how, which are also the activities that generate the most profit. We are good at conceiving and developing new products, providing the services that bring them to life and developing sophisticated approaches to promoting their brands. Our workers and businesses have established a global advantage by organizing multinational production networks, known as global value chains, around their products and then dominating the activities at the top ends of the curve.

This is why our national conversations about trade require nuance. We can’t simply focus on final or finished products. To understand how they were made and by whom, we have to think about the entire product journey…

…It may sound counterintuitive, but the more production processes are spread across national boundaries through global value chains, the more integrated the U.S. economy becomes with other economies in the world…

…[P]roducts are made through global value chains. Only one quarter of the goods and services traded globally are finished products. Therefore, the way we count the trade balance ignores that three quarters of global trade is in inputs or intermediary goods and services that make up parts of the overall production process.

While 70% of the value of a shirt might be added here in the United States, if it was stitched up in China and sent to us as a final good, China gets 100% of the value of that shirt credited to its export balance…

…Half of our imports go into making other products. Imports get a bad rap. However, like exports, imports benefit our economy; characterizing imports as a negative for our economy is too broad a generalization. To understand why, we need to know what we import and who imports it.

Half of the goods we import are orders from U.S. companies, primarily manufacturers, that import the inputs needed to operate their own production processes. Those imports consist of capital goods such as machinery and machine tools, semiconductors, parts and equipment, and industrial supplies including chemicals, fuels, lumber, plastics and metals.

American companies make myriad decisions about where to source appropriate inputs, ingredients and other supplies to make products, taking into account quality, price, cost and other criteria suppliers must meet. Having access to global suppliers means American-made finished products can leverage traded inputs when needed to be more competitive, which can help secure jobs for U.S. firms’ employees.

As consumers, we generally like the variety and buying power importing can deliver, from electronics to clothing to food. The cost savings for American families can be significant. Over the last 20 years, though wages increased, the cost of many non-traded items like healthcare services, higher education and housing increased significantly – out pacing wage growth. In contrast, prices in many traded items subject to import competition either stayed relatively flat or dropped. For example, the average price of a TV dropped 97%, software was 67% cheaper, and cell phone service became 52% less expensive. Trade creates competition but offers choice and saves the average American money by keeping consumer prices down.

About The U.S. Grains Council

The U.S. Grains Council develops export markets for U.S. barley, corn, sorghum and related products including distiller’s dried grains with solubles (DDGS) and ethanol. With full-time presence in 28 locations, the Council operates programs in more than 50 countries and the European Union. The Council believes exports are vital to global economic development and to U.S. agriculture’s profitability. Detailed information about the Council and its programs is online at www.grains.org.