Editor’s Note: The U.S. Grains Council recieved a note from the cattle finishers association of Northeastern Mexico, sharing their support for farmers in the flooding zones. Read the full letter here, which reinforces the strong partnerships built between overseas customers and U.S. farmers.

The floods of 2011 and 1952 were bad, but even the old-timers cannot remember when so much water flooded the Missouri River basin in southwestern Iowa. Significant flooding is also affecting other parts of the U.S. Corn Belt, including Nebraska, South Dakota and Wisconsin. Global Update talked with two farmers in the Iowa flood zone this week – past U.S. Grains Council (USGC) Chairman Julius Schaaf and USGC Director Duane Aistrope – to gain insight into the severity of devastation caused by the ongoing flooding.

In Fremont County, Aistrope said farmers estimate losing roughly 1.34 million bushels of corn and 390,000 bushels of soybeans stored in farmer-owned storage along the Missouri River bottoms. That estimate does not include additional elevators with significant bushels stored in bins and ground storage along the river.

“Thousands of acres just look terrible,” Aistrope said. “It looks like one huge lake down here along the Missouri River.”

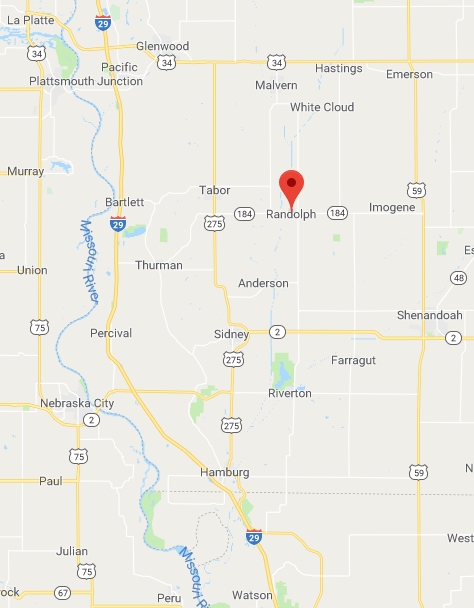

Schaaf and Aistrope are neighboring farmers, located near Randolph, Iowa – southeast of Omaha, Nebraska, and a short 20 miles east of the Missouri River. While neither farms directly on the Missouri River bottom, both have farmland along the West Nishnabotna River, which joins with an eastern branch before dumping into the Missouri River further south in Hamburg.

“When we get a big rip roarin’ flood and we have crops out, we lose about half our crop to the flood,” Schaaf said. “It’s been at least 10 years since we had one of those deals.”

A Wet Winter

Farmers like Schaaf and Aistrope, along with those in much of the Midwest, struggled to harvest their crops last fall due to rainfall and muddy conditions. Throughout the winter, southwestern Iowa saw above-average moisture. As a result, the soil was saturated and the waterways rose to higher than normal levels.

More snow accumulated and farmers thought winter would never end. Then, rain fell in the last two weeks – brought by the much-talked-about bomb cyclone. Five inches of rain fell during 60-degree weather, melting the snow. But, as the ground underneath remained frozen, the water ran off fields and into waterways instead of being absorbed into the soil.

The branches of the Nishnabotna River and the Missouri River flooded – quickly and severely. Neighbors, friends and family have lost homes, farmyards, equipment and more due to the rapid rise of the water.

“They did not even have time to get their equipment out, it just came so quick,” Schaaf said. “Nobody has ever seen something like this before – it just caught everybody off guard.”

Devastating Damage To Farms And Communities

Schaaf shared the story of a nearby family with a fairly new house and three small children. The family moved their belongings to the second floor as the water only reached the first story in 2011. This year, the water went higher into the second floor and they lost everything.

“They have nothing. It’s a bad deal,” Schaaf said. “And there’s thousands of those stories up and down the river – on the Nebraska side and the Iowa side. This is unbelievably cruel.”

Levees in the area continue to break. Schaaf and Aistrope sent trucks and generators down to help friends attempt to unload grain bins located on the Missouri River. Operations halted as levees broke and conditions became too dangerous to continue. The next day, the crew tried again to move more grain out – putting spotters on top of the levees.

“We couldn’t unload it fast enough,” Aistrope said, noting the team managed to move about 42,000 bushels of corn and soybeans out from his neighbor’s newly-built bins.

Surrounding towns are also continuing to see flood damage occur. The Army Corps of Engineers constructed a one-mile long wall of large sandbags covered in plastic through Hamburg. It gave way around 4:30 in the morning, leaving just enough time for Aistrope’s brother-in-law to get his mother-in-law – along with some clothes and paperwork – out of her house, located a block north of the barricade. Within an hour, the house was flooded.

“Everybody was trying to get out of the way of this thing in the short time they had,” Schaaf said. “It was fast and furious. I’ve never seen a flood come on so quickly, so intense.”

The record rainfall and flooding is also bringing a record amount of debris. On one 80-acre field, Schaaf said there are five or six acres of just corn stalks – piled three feet deep.

“There is more debris than I have seen for a long time,” Schaaf said. “All the corn stalks that got swept off upstream got carried down, hit a cross levee and just piled up. It’s the deepest and the thickest plant debris that I’ve ever seen after a flood.”

A Long Road To Recovery

Farmers will need to remove that debris from fields before they can plant this year’s crop. Conditions will need to be dry enough to use their tractors to move debris to the edge of fields.

“We just have huge drifts of wood and corn stalks and just all kinds of plastic and debris in almost every field,” Schaaf said. “And that has to get pretty dry before you can even begin to clean that up.”

Furthermore, broken levees mean sand moved onto the fields with the water, leaving three feet of sand on top of the soil in some places. Farmers will bring in equipment to push the sand into windrows – long piles that will stretch the length of a field – which will remain while farmers grow crops in between the rows. Eventually, the sand can be hauled out, but farmers cannot just return it to the river.

“That’s what people did in 2011 – farmers tried to incorporate it back into the soil. When the sand was too deep, farmers windrowed the sand and hauled it off,” Aistrope said. “What’s happened in a week’s time can take years to recover from. And this time is much worse than ever before. I’ve never seen anything like it in my life.”

A large share of acres will not be farmed in 2019 and possibly beyond as dikes may not be repaired for several seasons, leaving them open and subject to further flooding.

“No one can accept those kinds of risks with the costs of inputs so high,” Schaaf said. “No one can put a number on the acres that will be left idle this spring.”

The impact is devastating, both in southwestern Iowa and across the Corn Belt. As of press time, Iowa, Nebraska, South Dakota, and Wisconsin have all declared states of emergency related to the bomb cyclone and related flooding. The Nebraska Corn Board currently estimates potential impact to crop farmers across Nebraska at around $440 million. Impacts on overall acres continues to be assessed.

There is still time, however, for a share of the flooded ground to be reclaimed for a crop. East of the Missouri River bottom in Iowa, thousands of acres of rolling hill ground will eventually dry out for farmers to plant crops, hopefully in a timely manner.

“We generally like to plant corn from mid-April to mid-May in southwestern Iowa, and soybeans can do well planted from late April to early June,” Schaaf said.

While the local impact in the states affected by flooding is devastating, these areas represent a small portion of the total U.S. corn production acreage. Overall corn supply should not be in jeopardy as other production areas hold good potential for this year’s corn crop, thanks to the same ample moisture received over the winter.

Beyond planting concerns, homes, farms and communities will take time to rebuild.

“We can only do what Mother Nature allows us to do,” Aistrope said. “People’s lives are definitely never going to be the same – that’s for sure.”

Roads also remain underwater – inhibiting travel and causing concern for conditions when heavy grain trucks start to deliver grain again. Aistrope was forced to travel more than 30 miles to reach a flooded field located only five miles from his home as the roads in between were underwater.

These roads will still be in disrepair when farmers need move their grain from the bin to elevators and end-users. Aistrope delivers most of his grain north to Council Bluffs, Iowa – utilizing Interstate 29 to reach various destinations. To enter onto the highway, his trucks have to go north to Tabor and take a country road west to Bartlett. In Bartlett, only the roofs of the houses can currently be seen above the floodwaters.

And the alternate delivery route that runs by Glenwood? Also under water.

Spring Thaw Still To Come

More water is still to come as the normal snowmelt from Montana and the Dakotas does not typically arrive until June.

“This is just the beginning,” Aistrope said. “We still have the spring thaw that has to come our way. There’s a lot of stuff that has to come down this river yet.”

Snowmelt caused the last big flooding in 2011 and the great flood of 1952. The difference is that snowmelt flooding comes with advanced warning, sometimes up to a month in advance, providing time for everyone to prepare.

“They knew the water was coming in 2011. Everybody had time to get ready and take care of their stuff,” Schaaf said. “This time, there was no warning, no lead time.”

Despite these seemingly insurmountable odds, both Schaaf and Aistrope insist farmers and rural communities remain resilient and up to the challenge of recovering from this disaster.

“We can work through it,” Schaaf said. “It was a lot easier when I was a lot younger, but we’ll get it done. We always do.”

About The U.S. Grains Council

The U.S. Grains Council develops export markets for U.S. barley, corn, sorghum and related products including distiller’s dried grains with solubles (DDGS) and ethanol. With full-time presence in 28 locations, the Council operates programs in more than 50 countries and the European Union. The Council believes exports are vital to global economic development and to U.S. agriculture’s profitability. Detailed information about the Council and its programs is online at www.grains.org.