Editor’s Note: This is the second in a U.S. Grains Council (USGC) series exploring modes of transportation within the U.S. grain supply chain that provide a reliable supply of U.S. coarse grains, co-products and ethanol to the world’s market.

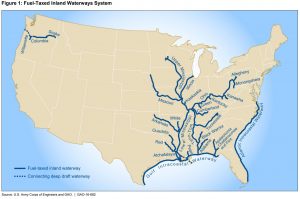

Flowing from farms in the Corn Belt down to the Mississippi River and into ports on the Gulf of Mexico, more than 12,000 miles of marine highways are a crucial part of the U.S. grain supply chain – one that has continued to operate in spite of the COVID-19 pandemic.

“U.S. geography happens to be extremely suitable for the ag trade and ag export business,” said Thomas Russell, president of The Russell Marine Group, who has compiled a monthly river condition report for the last 10 years. “The network of inland waterways and natural ports throughout coastal locations make water transport the most economical way to move large amounts of bulk grain.”

Easy Access From Farm To Port

Because inland waterways run through the U.S. Corn Belt, they provide easy access for grain to move through the system to ports of export and delivery to importing countries. The corn from Midwestern farmers can arrive in an import destination in Mexico just weeks after they deliver it to either a conveniently-located country elevator or a well-positioned river terminal. Inland country elevators also move grain by truck or ship to these terminals.

Whether delivered directly by a farmer or by another elevator, once the grain arrives at the river, it is loaded onto barges and down the river it starts to flow.

“Dozens of elevators are located up and down the river system,” Russell said. “These elevators act as collection points where the grain is usually loaded into barges and transported to the Louisiana Gulf, where it is transferred into ocean vessels and exported.”

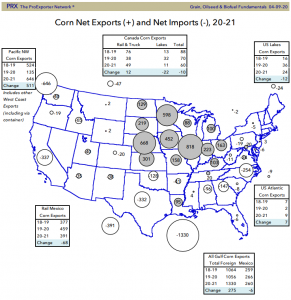

Ports on the Gulf of Mexico constitute more than 1.3 billion bushels (33 million metric tons) of demand for U.S. corn. Most of this grain moves downward through the inland waterway system and is destined for the export market. A combination of access, infrastructure and economics make logistics extremely efficient.

“Simply put, inland waterways transportation is the most cost-competitive way to move our nation’s bulk commodities,” said Deb Calhoun, interim president/CEO of Waterways Council, Inc. “The inland waterways move cargo in the safest, most energy-efficient, environmentally friendly way.”

From the barges on the river to the vessels at port, corn and co-products will move to destinations all over the world, including Mexico, Japan, South Korea, Spain and many others. This ocean transit is also highly efficient.

“Ocean vessels come in numerous shapes, sizes, and serve a multitude of purposes, some of which are highly specialized,” Russell said. “Shipping via water is reliable, most economical on a cost-per-ton mile basis, and fuel-efficient, producing a low carbon footprint.”

Shared Commitment Keeps Rivers And Ports Open During COVID-19

Despite the enormity of the U.S. inland waterways system, both Russell and Calhoun report the river and port systems continue to operate unhindered by coronavirus.

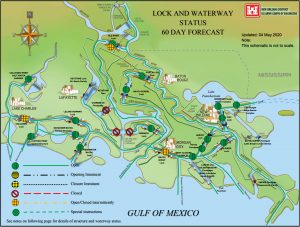

“Currently, all locks and dams are operating normally,” Calhoun said. “Companies, grain elevators and terminals and the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers are continuing to conduct business while closely monitoring their operations and workforce to keep employees safe and healthy.”

Russell reported that at the Port of New Orleans, everyone involved – loading terminals, grain houses, the U.S. Department of Agriculture’s Federal Grain Inspection Service (USDA’s FGIS), ship pilots, tugboat operators and all the vendors who participate in port activities – agreed to commit to keeping the port open in the interest of global economic and food security. The groups also worked together on building contingency plans, if needed, to address labor shortages or other needs.

“Everyone in the port got together early and committed to keeping the port open because we understood the importance of doing so,” Russell said. “The port is vital to the U.S. economy and vital to the world food supply.”

With that shared strategy in place, new policies and procedures are in place to protect workers from all nations. For example, the river and port pilots that safely navigate ships into and out of the port itself set up safety protocols for every ship to comply with, which were conveyed to ship owners and each individual ship captain. Those protocols included minimal personnel on a ship’s bridge when the pilot went on board, disinfection procedures and exchanging forms through a door instead of sitting together to complete necessary paperwork.

“There has been no disruption,” Russell said. “The pilots have been completely satisfied with what the ship owners and captains have been doing. Everyone’s trying to follow as best they can safety protocols and distancing. It’s worked, we have not really had any major problems.”

Russell reported there have been isolated incidents in which a crew member needed to be quarantined, or a terminal pulled a whole crew for isolation due to one member showing symptoms. But with a plan actively in place, at no time did these actions cause any interruptions to the grain supply chain.

“We’re all committed and, so far, it’s been working,” Russell said. “You’ve had some hiccups with personnel here and there that had to go to quarantine, so from time to time labor got a little bit tight. But at no point did the around-the-clock operations stop.”

High Water Conditions Signal Added Safety Measures

The coronavirus has not interrupted operations up and down the inland waterway, but the system has added extra safety measures due to high water conditions in the lower Mississippi River.

A weather pattern that started in December 2019 has caused excess rainfall up from Louisiana through the mid-South states like Arkansas and into the Ohio River valley. As a result, the lower Mississippi River is in flood stage from Cairo, Missouri, all the way down to the Gulf of Mexico.

Higher water conditions result in the institution of additional safety protocols throughout the river system and at the port, which can affect timing and costs. For example, reduced tow sizes mean not as much tonnage can be moved at a time. Certain cities institute daylight restrictions during high water conditions, meaning tows cannot run 24 hours a day through those safety zones. Once barges are delivered to the Gulf, more tug power is needed to distribute the barges to various terminals, because tugs cannot leave the holding fleets of barges.

There’s also additional cost for incoming ocean vessels. For example, a pilot may be required to be on board at all times at certain depths – adding costs – and extra tug power may be needed to move ships in and out of berth.

But Russell is quick to point out this year’s conditions are not as devastating as last year’s spring flooding disasters. Last year, rain fell across the river system and its tributaries, causing stress and eventually flooding throughout the entire system. This year, the excess rainfall is concentrated on only the lower half of the system, which is better able to handle the moisture.

“We don’t have the additional snowpack up north, and we don’t have the additional rain that was hitting the Midwest with the same velocity that was hitting the South,” Russell said. “The high water is concentrated right now on the lower Mississippi River. The closer you get to the Gulf of Mexico, the deeper and wider the River gets, so it’s in better shape to absorb and handle big rain events because it flushes quickly. That doesn’t get us out of high water, but the River can take more of a massive amount of precipitation compared to other rivers and other areas of the country.”

Marine Highways Remain Economical And Timely

Despite the additional time and cost due to high water conditions, which have been declining in recent weeks, the inland waterway system is still a solid economic option, and most customers are used to the adjustments due to high or low water conditions. The extra safety protocols in place only add a few extra days from delivery of a barge from the interior to the port.

“The rule of thumb is from St. Louis to the Port of New Orleans is seven days,” Russell said. “Everything in high water moves a little slower, but only adds an extra three or four days from point of origin to delivery to the final terminal. The slowdowns have not been costly enough to cause any real convulsions.”

Calhoun mentioned there is a scheduled maintenance shutdown of the Illinois Waterway starting in July that will extend through September but noted the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers is communicating with industry about what to expect during the closures. Overall, she emphasized, the inland waterways system is operating and will continue to play an essential role in moving grain from the farm to the port and off to export destinations.

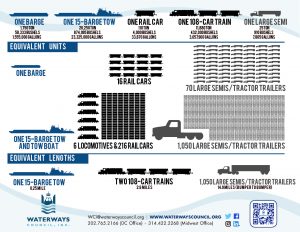

“There is a misconception that if the inland waterways were not available as a transportation option, grain could move by truck or rail,” Calhoun said. “But the fact is that there is not nearly enough capacity to move U.S. exports of agriculture (and other) commodities without the river. All modes of transportation must operate as efficiently as possible in the intermodal supply chain, but the river offers effective, competitive and much-needed capacity.”

The inland waterways system is a critical artery in the U.S. grain marketing system, necessary to competitively serve global markets for corn and other coarse grain and co-products. This year is no different as the river and port systems continue to operate in spite of a global pandemic and high-water conditions.

About The U.S. Grains Council

The U.S. Grains Council develops export markets for U.S. barley, corn, sorghum and related products including distiller’s dried grains with solubles (DDGS) and ethanol. With full-time presence in 28 locations, the Council operates programs in more than 50 countries and the European Union. The Council believes exports are vital to global economic development and to U.S. agriculture’s profitability. Detailed information about the Council and its programs is online at www.grains.org.