How drought will affect Mexico’s demand for U.S. feed grains is hard to assess, but the impact is likely to be felt for two to three years, according to Julio Hernandez, who directs market development programs in Mexico for the U.S. Grains Council.

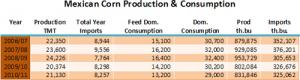

The drought, part of the same weather system that devastated Texas and nearby states last year, is Mexico’s worst in 70 years, according to Ignacio Rivera, the country’s undersecretary for rural development. Rivera predicted it will lower corn production for the current year to only 780 million bushels, compared to 830 million bushels in the 2010/11 calendar year.

Current grain shortages could push Mexico’s imports this year above 9.5 million metric tons (374 million bushels) of corn and sorghum purchases above 3 million tons (118 million bushels), Hernandez said. Mexico is already the second-largest customer for U.S. feed grain exports and a leading buyer of distiller’s dried grains with solubles.

“Problems began last year when severe frost damaged Mexico’s corn. That foced Mexico’s tortilla manufacturers to look for other sources of white corn,” Hernandez said. “In an attempt to minimize these losses with replanting, the government sent additional water from the reservoirs. Now Mexico is suffering because it doesn’t have enough water in the reservoirs for this year’s crop.”

While crop losses are likely to create more demand for U.S. exports, the drought-related losses in the livestock sector are a potential offset. Mexico’s ministry of agriculture estimates that 60,000 cattle have died and an additional 89,000 have been culled by producers.

Livestock producers say it will take as much as three years for herds to recover.

“Those cows that were lost are not going to produce calves, and the period those calves need to grow is about three years,” said Alvaro Ley, president of the Mexican Cattle Growers Association.

The most serious problems are in northern Mexican states like Sinaloa, Zacatecas, Chihuahua and San Luis Potosi, where many cattle producers have small, open-range operations of 20 cows or less, according to Hernandez. Jalisco, Mexico’s leading agricultural state, was much less affected.

“My impression is that the large commercial operations took steps to buy corn from other parts of Mexico like Oaxaca and Chiapas. That was not enough, so there were additional imports of grain. Now we are seeing more purchases again. Companies are buying corn and sorghum in January or February instead of April or May,” Hernandez explained.

“It will be really hard to tell exactly what consequences this will have,” Hernandez concluded. “If you ask the feedlots, they are doing a lot to recover, but we will be missing some cattle numbers for the next two to three years.”